C.S. Lewis similarly expands our view of Aslan’s operations in The Horse and His Boy. To do this, Lewis doesn’t take us to the land of giants or to mysterious islands in the uttermost east. Rather, the beginning pages of The Horse and His Boy direct our attention to an unremarkable fisherman’s hut. What could be of interest here? It’s not a promising start to an adventure. But looking back from the vantage point of the end of the story, we see Lewis’ goal: to show that Aslan is intimately concerned in the lives of each of his creatures, even the forlorn, adopted son of a fisherman.

We first meet Shasta, our flawed hero, in humble conditions—little better than a slave—but over the course of the story he becomes an heir to a kingdom. Along the way, Shasta’s character accordingly grows in stature as he learns loyalty, courage, and sacrifice. Shasta’s fellow travelers experience similar transformations.

What ties these characters together is that they have grown up outside Narnia without knowing Aslan. But he is mindful of them, and he cares for them. They are under his tutelage even though they are not aware of it. At some point in the story, each of them have an encounter with Aslan where they learn of his interest in their lives, and it’s a revelation for them and for the reader: the mysterious lions that have intervened in their adventure have really been just one Lion all along!

The lesson that Lewis seeks to impart (he is teaching morals to young people, after all) is that God knows and loves each person and has a plan for their lives, even those who don’t know him. It’s as if Lewis takes us far out of our solar system, to another planet where we can see and feel another landscape and atmosphere. We might feel overwhelmed, exclaiming with the Psalmist, “When I consider your heavens, the work of your fingers … what is mankind that you are mindful of them, human beings that you care for them?”

Then we look down and Lewis gives us the ability to examine the molecular composition of an extraterrestrial rock, then even deeper to observe subatomic particles in their constant dance. “See!” he exclaims, “See how God neglects no detail but upholds even these small things in every place.”

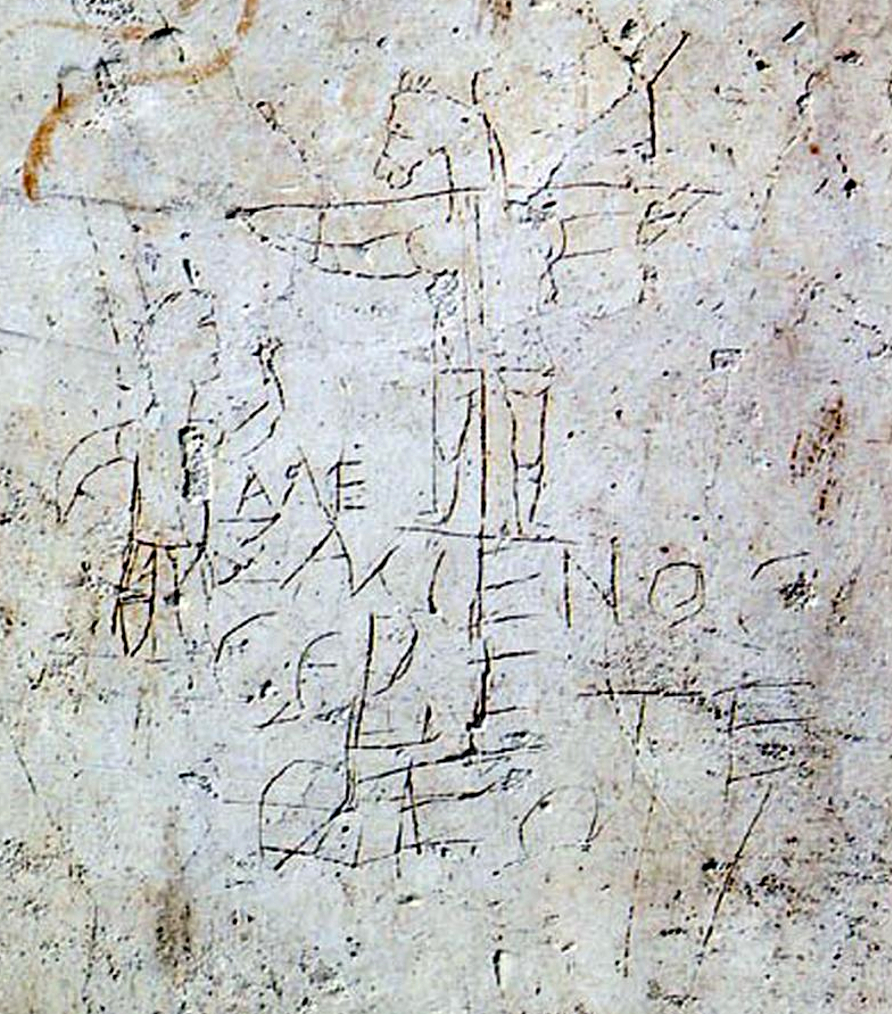

This type of extending, pervasive divine interest is entirely biblical. Consider Ruth, a poor foreigner in Israel, who finds the favor of the Lord and becomes ancestor to the king. Or Hagar, an Egyptian slave who runs away into the desert, fleeing her cruel mistress. She is surprised to meet God there and names him El roi, “the God who sees.” God sees every runaway slave.

In The Horse and His Boy, Aslan’s involvement is primarily about discipline. Not only punishment (though that might be part of it), but training. My favorite scene of the book is when Shasta arrives breathlessly at the Hermit of the Southern March after heroically saving Arvis from a lion. They are racing against time and must warn the king of Archenland about the invading Calormene army.

“Are—are—are you,” panted Shasta. “Are you King Lune of Archenland?” The old man shook his head. “No,” he replied in a quiet voice, “I am the Hermit of the Southern March. And now, my son, waste no time on questions, but obey. This damsel is wounded. Your horses are spent. Rabadash is at this moment finding a ford over the Winding Arrow. If you run now, without a moment’s rest, you will still be in time to warn King Lune.”

Lewis describes Shasta’s silent struggle upon hearing this. The demand seems cruel and unfair after all he’s been through. “He had not yet learned that if you do one good deed your reward usually is to be set to do another and harder and better one,” Lewis writes. You sense this is perhaps the most important test for Shasta so far, and you’re cheering for him along with the angels in heaven. “You can do it, Shasta!” Your heart thrills when he answers only, “Where is the King?”

For believers, The Horse and His Boy can be the most intimate of the Narnia stories. We learn that every person has their own story that God is writing together with them. In the midst of confusion, we can rest assured that God indeed has a plan but that it's not always to make us comfortable, but better.